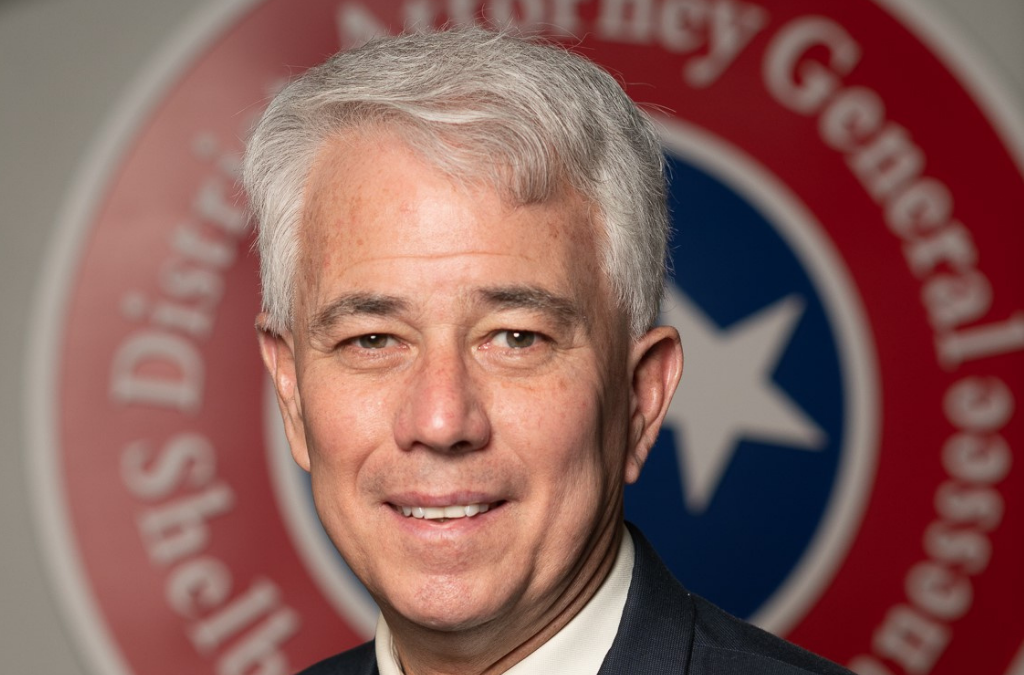

Shelby County District Attorney, Steve Mulory, in an exclusive interview with Bluff City Magazine gives insight in the D.A's office, the judicial commission, bail, crime deterrent and racial disparities among the African American communities.

Steve, thanks so much for meeting with us. You've been in office for six months and you've been tasked with some monumental cases and trials and tribulations here. How are you feeling? How are things going with six months into it?

I'd say so far so good. I’ve been pleasantly surprised by very supportive staff. No sense of resistance to change. Being the new guy can be viewed with skepticism. They've been very friendly, supportive, and open to my new ideas. But it has been baptism by fire. My second day in office was the Elizabeth Fletcher kidnapping. That first weekend was when we were praying that we found her alive. Then everyone kept telling me, this is a once in a decade case. It's not normally like this. You're not going to see anything like this for a long time. Then several days later, Ezequiel Kelly went on a murder spree.

My goodness, you’ve really been thrown to the wolves!

Right, exactly. I think we handled it as well as we needed to. Then I thought things calmed down for a while. Then December was Officer Involved Shooting Month. We had four different Officer Involved shootings. I was woken up at 2 AM, 4 AM. Seemed like every weekend with a call. Do I call on the TBI? Then finally we thought, okay, New Year, January, a fresh start, maybe things will calm down. And then Tyre Nichols. So, it's been a lot. It's been an intense six months.

You were a former law professor. Former federal prosecutor where you worked under the Clinton administration. I think we talked about that on my radio show. So, you've got a lot of experience. Was any of this a learning experience for you?

Oh, absolutely. I know criminal law and I know how prosecution works. I've been around in Memphis long enough to have some sense of the Shelby County criminal justice system. But there's no substitute for seeing the day-to-day nitty-gritty details of how General Sessions Court works and how criminal court works and what goes through the process of getting an indictment and all those kinds of things. But fortunately, as I said, I've got a really supportive staff that has been showing me that nitty-gritty detail. I think I'm learning a lot about how to manage expectations, about what the prosecutors can and can't do, about dealing with victims and victims’ families and managing the media and public expectations. So many high-profile cases in which this intense public interest and you've got to be transparent. But at the same time, there are limits as to what a prosecutor can say. I’ll be striking that balance as best as possible.

You mentioned you have a supportive staff. When this office changed from a Republican DA to a Democrat DA, were there a lot of people who left on their own, or have you seen a lot of transitioning from attorneys that would be more in line with Democratic views versus Republican views, or have a lot of them stayed on? Tell us a little bit.

I was the first Democratic DA in Shelby County history, or at least the modern era anyway. It was a big change. And to my surprise, only one or two attorneys left because of the change in the administration. People are constantly leaving when you're hiring and this attrition and everything, but all for independent reasons. They're moving out of town for family reasons, or they got snapped up by a private firm that paid them so much that I can't compete or something like that, not related to the election. Only one or two I think left because of that. I expected a certain amount of resistance, a certain amount of digging in because other reform prosecutors have had that experience around the country. I didn't have that. I did decide that there were a handful of lawyers that I thought needed to move on because I needed people who were going to be enthusiastic about my reforms. But we've had a lot of turnovers just through life. We've also done a lot of hiring and we've put a real emphasis on increasing diversity.

One of the things the public is really concerned about right now is seeing repeat criminals released back into the public. I know you're implementing the bail reform that's going on, can you tell me your insight of these concerns and stories that we see about people that are often habitual criminals? For example, the young man who was only 11 years old that had been in and out of jail with multiple convictions but kept getting released.

I'm going to start by referring you to an op-ed that I did a few weeks ago. It was on the front page of the commercial appeal viewpoint section, in April. I think it provides a lot of useful background and it's very short. But a couple of things. First of all, the DA doesn't set bail. People don't understand that, but it's true. The judge sets bail. A lot of these high-profile cases have gotten attention in the last couple of months, including that 11-year-old, the Whitehaven Lounge shooting, and the murder of Pastor Autura Eason Williams. In a lot of those cases, our office opposed the pre-trial release and opposed the reduction in bail. But there's a broader point because I don't want to be understood as just saying, “Oh, it's just those horrible judges.” That's not what I'm saying. People think that bail is supposed to be used as punishment, and it's not. Under our constitution, you presume everyone is innocent until proven guilty. The only reason you keep somebody behind bars before their trial, before they're convicted of a crime is because either you believe they won't show up for their court date, they'll flee the jurisdiction, or you think they're a danger to the community.

Essentially this means they don't have anything. Their life is gone, right?

Exactly. The new bail system was supposed to address that problem. Now, it was adopted by the county to avoid a lawsuit before I took office. I had nothing to do with it, although I do support the concept. I will note that both Amy Weirich and I both testified in favor of the new bail system to the county commission. The new bail system does provide a hearing. It says within 72 hours, these people are going to get a hearing. They'll have a lawyer with them. The prosecutor will be there. There will be a judge. The judge will look specifically at the defendant's finances to figure out what they can afford and what they can't afford. Then they won't do an unaffordable bail, which is basically saying you don't get out unless we can prove that the person is not likely to show up for their next court date or is likely to reoffend. I think that's appropriate under the Constitution. That's supposed to be what happens. We are really basically just conforming our system to what the law requires, except we weren't obeying the law previously.

Now, is there a big problem with people reoffending right after they get out?

Actually, no. There have been a few high-profile cases like I said, where we thought the judge got it wrong. We understand why people are upset. But if you take a look at the data, it's actually not that frequent that people re-offend while they're out on bail. I addressed this in the op-ed. In the last two years, people have committed any kind of offense less than 23% of the time when they're out on bail. That includes minor offenses. They re-offend violently only about 3.6% of the time when they're out on bail. Now, I would like to push those numbers down. They should be zero, right? But remember, you've also got to make sure that you're not keeping people behind bars who are innocent for all those reasons I said earlier. So, you've got to balance those two things. I think there's room for improvement, but I also think there's a lot of misunderstanding about our bail system.

Was it a fluke as to why the 11-year-old juvenile kept getting out even after all the convictions?

Yes. But I think it was partially because he was a juvenile. We're trying to be more lenient with juveniles. The point of the juvenile justice system is to rehabilitate them while we still can. Contact with the criminal justice system interferes with that. So, to the extent that you can put them back in their home or in a supportive environment, stay in school, counseling, whatever, that's better for juveniles. Now, in that particular case, I think we had decided that enough was enough, and the judge disagreed. But I think those are outliers. I don't think that's the normal case.

For those violent offenders who keep getting released, is that due to the laws that are on the books and have to be followed by the judicial commissioners who are setting the bail based on the state law?

It's judicial commissioners that make the call. They will probably look at to what extent the person has ties to the community. To what extent are their priors, violence versus other types of things? Is there some other arrangement that would be less restrictive that would serve the public safety needs, like an order of protection or an ankle monitor or that sort of thing? The idea is that locking people up when they haven't been convicted of a crime is supposed to be a last resort. The judicial commissioners are going to look, do they have ties to the community? Is there someone who will vouch for them, and sponsor them? Will an ankle monitor help? Will an order of protection help? How many times have they re-offended? Are we really convinced that this person is not to be trusted? I think our office and the judicial commissioners don't always see eye to eye on it. There have been a few cases where we've been a little displeased. But I don't want to go from that to a wholesale condemnation of the idea of bail because like I said, I think most of the time people aren't reoffending while they're out on bail.

Recently, the city council passed an ordinance about police no longer pulling people over for small violations such as expired tags, broken taillights, and other minor offenses. Many people are saying they feel like law enforcement officers are getting their hands tied more and more – and not being able to enforce the laws on the books. But when we look at the incident with Tyre Nichols and what happened there – a small violation led to him being pulled over - they wouldn't have been able to pull him over under this current directive. What is your opinion on that?

I think the Tyre Nichols experience dramatizes the need for police reform, including the type of police reform you just mentioned in the ordinance. What we find from the data is when police pull people over for these really, minor things, they're doing it disproportionately to young black men because they're hoping that it will turn into something else. So they think, Oh, we'll pull them over for this. Maybe we'll find a gun, or we'll find some weed, and then we can make a real bust out of it. But they don't do that to people that look like you or me. It becomes a real problem because if you have over-policed minority communities where this enforcement behavior is happening over and over again, then you have repeat players who are being victimized by it. Then that incurs resentment among the community and the community is less likely to cooperate with law enforcement. I'm talking about providing tips, reporting crime, serving as witnesses, and that is really what you need if you're going to bend the curve on violent crime. The game is not worth the candle because the data shows that the vast majority of the time, you don't find the lead, you don't find the gun. You have alienated them. And all the time you’ve spent doing that, you could have spent investigating actual violent crime, patrolling neighborhoods, and helping keep neighborhoods safe.

One of the things that I've said to people - and it really seems to be something most people support – is we need more crime deterrent methods in place. Back in the day, you had a police officer just driving up and down your neighborhoods, checking in on the households, because if you had that, it would deter people from breaking into cars or trying to break into homes.

What you're referring to is what's now called community policing. There's a lot of evidence to suggest that that really helps. You have them in the neighborhood, just patrolling, checking in, getting to know people, and developing a sense of trust so that then they will provide tips that help prevent crime.

Six months into it, you’ve got a long way to go. Your term is eight years. It may be too early to ask, but do you see yourself running again at the end of those eight years?

I don't know, it's a good question. I didn't run as a career move. I was very happy as a tenured law professor with summers off. I was recruited to run because there were people who felt like we needed change and we needed reform. If I feel like I have implemented the reforms that I hope to get implemented in eight years, such that they're going to stay in place without me, I could very easily see myself saying let’s enjoy life a bit.

More free time on your calendar, I'm sure!

There's an awful lot of Star Trek out there that needs to be watched.

In closing, what would you like to see accomplished in the next 7 years? What would you see as the legacy of DA Mulroy?

I would like to look back and see that the rate of incarceration, particularly for minor offenses, has lowered. The amount of time people spend in jail waiting for their trial has been lowered. Racial disparities across the system, from bail to charging decisions, to racial profiling, to sentence disparities have been significantly reduced. Also, the curve on violent crime has flattened and started a downward trend. I'd like to see all of those things happen. I'd also like to see the number of times our office has been cited for ethical violations be dramatically reduced because this office was pretty high.

I think whenever I had you on my radio show last year, you mentioned that the previous DA and her office had a review and this office was seen as one of the worst DA’s offices in the USA. What were the terms of that?

There was a Harvard Law School study that said that of the four states that were studied, this office was the worst for a number of convictions that were overturned due to prosecutorial misconduct, and ethical violations by the prosecutors. I would like our office, at the end of my first eight years will have a reputation for being the leader when it comes to transparency and ethical conduct, cooperation with the defense and with the judges. All those things I think would be nice to be able to look back after eight years and say we've got there.

I love it. Anything you want to add?

Well, just that we're being incredibly transparent. We're starting press conferences every two weeks. We'll announce whatever we have to announce, but it's mostly just “come with questions”. I'll be doing town hall meetings at different parts of the county every other month. And we're establishing a series of partnerships that I think are useful. We just recently announced a partnership with MPD to tackle organized retail theft, all these groups of people ramming into storefronts, etc.

We've established a previous partnership with MPD on a cold case unit. We are right now working with a national group called Justice Innovation Labs, which is a group of data experts and former prosecutors whose specialty is advising DA offices on how to best use their data. They're going to come in over the next 12 to 18 months and up our game, clean our data, make our data reliable, teach us how to do data-driven decision-making, and then be as transparent with their data as possible. So, we'll have a public-facing dashboard on our website by the end of this process that anybody can access to get the data that they need. Those are just a few of the initiatives.

Thank you for meeting with me and Bluff City Magazine for insight into your role, your job, and your office!